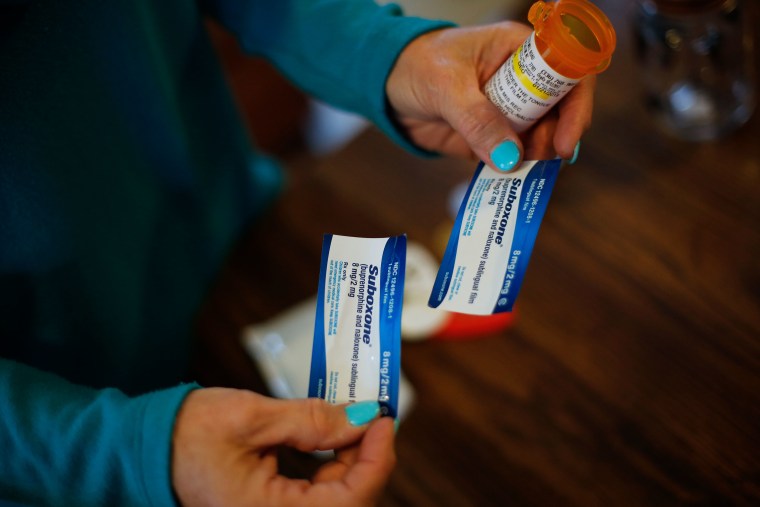

When Daniel Patrick Garrett began using Suboxone three years ago, he spent hours driving to find a pharmacy that would accept his prescription for the opioid use disorder treatment.

Eight couldn't or wouldn't fill the prescription, Garrett recalled. A ninth would, but wouldn't accept his discount card, something that the uninsured 27-year-old needed to use to afford the medication. Finally, at the tenth location, a Kroger about an hour from his home, they were willing to fill the prescription and accept the discount.

"I broke down crying because I was so happy that they would just fill it for me," Garrett, based in Jackson, Tennessee, and the director and founder of Tennessee Harm Reduction, told TODAY.

Now, he uses methadone, another similar medication. While he no longer has to do the two-hour round-trip drive to a pharmacy, he does have to drive to a local clinic five days a week to take doses of the medication under supervision. While the ride is only about five minutes each way, the near-daily attendance (the clinic is closed on weekends) and limited hours can make it difficult. Clients waiting for the clinic can spend up to an hour in line, which can result in comments from passersby and public stigma.

"I wish it wasn't like this," Patrick said.

What is medication-assisted treatment?

Medication-assisted treatment, also called MAT, is a way of treating opioid use disorder. "The prescribed medication operates to normalize brain chemistry, block the euphoric effects of alcohol and opioids, relieve physiological cravings, and normalize body functions without the negative and euphoric effects of the substance used," explains the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The two most common medications used in this form of treatment are methadone and buprenorphine, said Dr. Steve North, a family medicine physician in Asheville, North Carolina, specializing in addiction medicine. A third option, naltrexone, is used less frequently because it requires patients to fully detox beforehand, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

North explained that buprenorphine is a partial-opioid agonist, which means that it occupies the receptors of the brain affected by opioid use without giving the same effects.

"By occupying that receptor site, the craving (for illicit, full-agonist opioids) is decreased," he said. Suboxone, the brand name version of buprenorphine, also includes naloxone, which can reverse opioid overdose.

Methadone, on the other hand, is a full-opioid agonist, meaning that it has similar effects to illicit opioids, like fentanyl and heroin, and can cause overdose, North said. However, methadone is more "regulated" than those illicit options, he explained.

"Because methadone is an FDA-approved drug, the supply is much safer," North said. "Additionally, it lasts a very long time in the body, so there is not the roller coaster effect of ups and downs that happen with a shorter-acting drug," like fentanyl or heroin.

Methadone's effects last about 24 hours, which is why patients need a daily dose, North said. Avoiding the "ups and downs" means that people are stable throughout the day, and methadone also helps reduce cravings, he added.

Studies show that access to medication-assisted treatment can reduce overdose deaths: One that looked at heroin overdose death rates in Baltimore from 1995 to 2009, found that overdose deaths dropped by 37% after buprenorphine became available in 2003. Both buprenorphine and methadone have decades of research supporting their use, as the latter was approved by the FDA in 1972, while Suboxone and a similar product, Subutex, were approved in 2002.

That said, only 11.2% of the 2.5 million people 12 and older who had an opioid use disorder within the past year received MAT within the past year, according to 2020 data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, conducted by SAMHSA.

“We’ve heard a lot about structural stigma,” said Sheila Vakharia, Ph.D., deputy director of the department of research and academic engagement at the Drug Policy Alliance. “Methadone and buprenorphine are two life-saving medications that are treated distinctly different from every other medication that’s prescribed in this country. So much of how we manage these medications builds in a stigma that includes having to jump through a lot of hoops that can deter people from wanting to deal with it to begin with.”

How do barriers impact use?

A 2021 study published in the Journal of American Pharmacies Association explained that access to buprenorphine formulations, which require a prescription to access, can be “uneven” due to “perceived and actual regulatory constraints, training gaps, stigma, and challenges to (the) prescriber-pharmacist communication limit.”

Methadone is a Schedule II controlled substance, meaning it has "a high potential for abuse which may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence," per the Drug Enforcement Administration. Other medications that meet this same standard include oxycodone and Adderall. Because of fears that methadone could be misused, regulations set by the Department of Health and Human Services, the DEA, SAMHSA, state authorities and others require most methadone patients pick up their dose daily, in person, Vakharia said.

These steps are meant to make sure the medications are being used appropriately and prevent diversion, or the misuse and resale of those substances, Vakharia said, adding that research shows that diversion is "much more rare than people might think." According to a 2021 report by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, methadone diversion is most common when the drug is used to treat pain, not opioid use disorders. And when diversion does occur in the latter situation, it's due to "a lack of access to medication ... which aligns with other findings that 80% of people who report diverting methadone did so to help others who misused substances," the report stated.

Vakharia and North both said that the daily visit structure for methadone can make using it consistently particularly difficult, but it's important to do so as missing a dose can cause withdrawal. Sometimes, patients have to wait outside, leaving them exposed to the public eye. Johnny Sudds, who has been taking methadone since 2014, said that having to line up in public adds a feeling of “shame.”

“You’re standing in front of people, who can see you. ... Everybody knows the methadone line,” said Sudds, 71. “They look down upon us. People are trying to do something right, and they’re being ostracized.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration loosened their guidelines to allow patients defined as "stable" to receive up to 28 take-home doses of methadone. To meet the definition of "stable" under this policy, patients must meet eight qualifications, including "a minimum of 60 days in treatment," negative toxicology tests, and "total adherence" to their treatment plan," per SAMHSA.

David Frank, Ph.D., a medical sociologist and research scientist at New York University's School of Global Public Health who's used methadone for 20 years, said that his clinic's policies consider him "stable" and allow him to receive a month of take-home doses at a time, making it easier for him to achieve goals like earning his Ph.D. However, he still sees the impact that the daily requirement has on people like Garrett, whose program is open from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m.

"Imagine if you had to go somewhere every single day at 6 in the morning how that would interfere with anyone's life," Frank said. "It's ironic because clinics want you to do things like get a job or go to school, but their very policies make that impossible."

Despite the hurdles associated with each medication, some people who use medication to handle their substance use still see it as life-changing. Sudds said the use of methadone made it possible for him to stop using illicit morphine, which he had been dependent upon since the 1990s.

“Suboxone has been really stabilizing and kept me from spiraling into a crisis,” said Sessi Blanchard, a drug policy community organizer at VOCAL-NY, who still uses some substances in addition to Suboxone. “That’s been the main benefit. It’s definitely resulted in me using less (illicit drugs) because I feel stable. (Because Suboxone contains naloxone), the biggest benefit of me using Suboxone is that I have never overdosed from an opioid, which is very rare and pretty miraculous.”