In years past, the governor and leaders of the Senate and the Assembly—the proverbial “three men in a room”—worked the tangle of bills and resolutions into a budget, an often opaque process. While the optics are different this time, some budget experts say they don’t expect the process to change dramatically.

Flickr/NYS Media Services

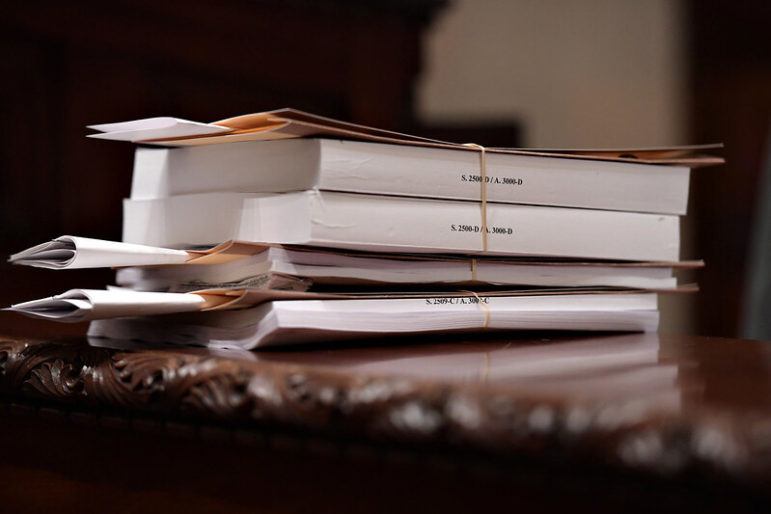

State budget bills in the Senate chamber during 2021 legislative session.Lea la versión en español aquí.

In just under a week—or no later than the second Tuesday after the first legislative session of the year, according to state law—Gov. Kathy Hochul will introduce her executive budget, a package of appropriations bills for the state legislature to review.

We got a preview of the governor’s upcoming policy agenda last week at her first State of the State address, in which she pledged to usher New York into a new era.

After the governor introduces the executive budget, state leaders will start an intense negotiation process, good government experts told City Limits: New York’s state Senate and Assembly have until March 31, the end of the state fiscal year, to adopt a budget, one of the narrowest windows of any state in the U.S., said Rachael Fauss, a senior analyst at Reinvent Albany who focuses on the state budget.

“For the budget to get introduced in late January and then adopted by April 1 is an incredibly short timeframe for a budget to be adopted,” Fauss said. “It’s unusual in the whole country—usually there’s more time.”

Even New York City’s budget is worked out over a longer period, she noted, usually between February and the end of the fiscal year on June 30.

In years past, the governor and the leaders of both the Senate and the Assembly—the proverbial “three men in a room”—worked the tangle of bills and resolutions into a budget, an often opaque process. Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo was known for exerting tight control over budget negotiations, and Hochul, who took over after his resignation, has vowed to be more transparent.

“The days of New Yorkers questioning whether their government is actually working for them are over,” she said during her State of the State speech. “And the days of three men in a room are clearly over.”

While the optics are different this time, too—Hochul and Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the Senate majority leader, are women, and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Stewart-Cousins are Black—some budget experts say they don’t expect the process to change dramatically.

“The idea that three people of any gender would be, effectively, negotiating the entire budget, without much input from anyone else—I think that’s still the case,” said Bill Hammond, senior fellow for health policy at the Empire Center. “I don’t think that’s fundamentally changed.”

City Limits asked the two watchdogs to answer some frequently asked questions about the oft-confusing New York State budget, how it gets shaped and what it means for residents.

Just how big is the state budget?

New York State has one of the biggest budgets in America, a figure that has grown in the past decade and is expected to get bigger. Last year’s budget agreement sat at $212 billion, the largest in New York history and 10 percent bigger than the one passed the year before, bolstered by $12.6 billion in federal pandemic relief aid. Another big infusion of federal dollars is expected this year, experts pointed out, part of emergency aid packages related to COVID-19 recovery.

How does state leadership determine how much money we have and can spend? Where do these numbers come from?

“The governor will have the executive number, the estimate of how much money is going to come in for the year,” Fauss said. “But there’s also a role for the state comptroller, and the legislature—both the majorities in each house and the minorities in each house have their own forecasts for how much money they think the state has.”

Those talks typically began at the end of the calendar year, and are already underway, she added.

“Now it’s gonna be the sort of wrangling between, ‘Well, how much money do we have, and how much money are we going to spend?’” Fauss said. “And keep in mind too, that they can raise new taxes and they can make more money if they want to, or they can do tax cuts and have less money to work with—that’s probably not going to happen.”

How does the governor officially present the budget?

“The budget process starts with the governor proposing a set of what are called appropriation bills, and what are called Article 7 bills, which are the changes to law that are necessary to make the budget work,” Hammond said.

These bills, which are broken into broad areas like education or health care, are each hundreds of pages long. Careful readers will note that New York’s governors have “gotten into the habit of piling in a whole bunch of non-budgetary things into those Article 7 bills—which to my mind is an abuse of the process,” Hammond added. “But it’s useful politically, especially to the leaders of the legislature. So they have not resisted adequately to prevent it from happening.”

After it’s submitted in January, the governor can add or change things from the proposed budget though a 30- or 60-day amendment process.

What role do lawmakers play in the process?

Lawmakers can hold hearings on the separate segments of the proposed budget, experts said.

Sometime generally around mid-March, legislators in both the Assembly and the Senate officially respond to the executive budget with what is known as a “one-house bill”—which, confusingly, isn’t exactly a budget bill, but a resolution that reflects each chamber’s budget priorities.

“In some cases, the Senate and Assembly may be aligned and they’ll be introducing the same things, and in other areas, they may have new things that they want, that one house thinks is important, and the other does not,” Fauss said.

As part of this, legislators can propose new appropriations, add to a particular line item, or add money to a line item in a proposed budget, Hammond said. That’s subject to line item veto by the governor, but legislators can also simply reduce the amount of money allocated to an item—“which the governor has no way to stop,” Hammond added.

“If she proposed, say, a billion dollars for child care, and the legislature for whatever reason reduces that to $500 million, $500 million is the last word. If both houses of the legislature make that choice, the governor can not veto that, the way the Constitution was written.”

As a practical matter, though, this “almost never” happens, per Hammond, who noted that “the legislature generally wants to spend more than the governor proposes.”

So how does everything get finalized?

To ultimately get a budget adopted, state legislative leaders and the governor come together to bargain on the specific language and dollar amounts that will make it into the final budget bill, which is subsequently revised by the governor and then voted on by the legislature.

“That’s where the ‘three men in the room’ [trope] comes from,” Hammond said, saying the Senate majority leader and the Assembly speaker make their final negotiations at this point. “In effect, they go to the governor and they say, ‘We want to do this childcare proposal you’re talking about, but we don’t like the restrictive language. If you take that restrictive language out, we will give you the money you want.’ The final stage of the budget consists of the governor re-submitting proposed legislation under her name.”

Budget watchdogs stress that this is an intensive, and sometimes troublingly secretive, procedure. While Hochul has projected a desire to collaborate more with the legislature than her predecessor, experts are unsure if this will result in a more transparent process.

In the 15 years that Fauss, of Reinvent Albany, has been following the state budget, she noted that “things don’t happen till the 11th hour sometimes, and sometimes that has been by design, so that the negotiations happen at the last minute.”

Because of this, she said, members of the legislature and the public have “very often had to rely on the leaders to kind of explain to them what got changed,” in a massive budget bill, stifling transparency and enabling secret, back-door deals to be made.

“That has been too often kind of the way that it happened in the past,” Fauss added. “I think a judge of this process and how collaborative it is, and how transparent it is, is to not have these last-minute frenzies where deals are cut and legislators can’t even read the bills before they vote on them.”